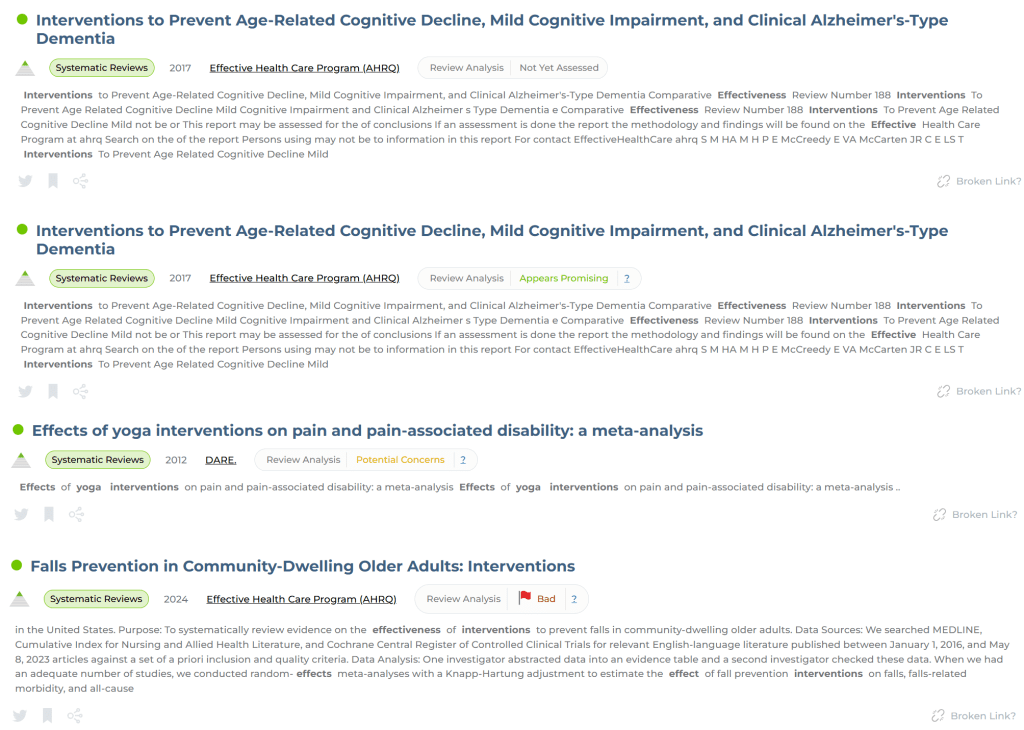

In our previous post we used AI to prioritise research priorities for Parkinson’s Disease. But how do we judge if it’s any good? Well, we went and explored the literature and found this 2024 paper in Nature Reviews Neurology Parkinson disease therapy: current strategies and future research priorities. It is unclear how they arrived at their list, I assume expert opinion.

But the comparison—using ChatGPT—is fascinating. Not just in terms of where they align, but also in their differences. For me, the standout difference is that Nature Reviews Neurology places a strong emphasis on interventions such as pharmaceutical drugs and surgical treatments. This seems intuitively correct, but it also reminds me of Iain Chalmers’ work on research prioritisation.

Iain has done extensive work in this area and was the driving force behind the James Lind Alliance. In his 2015 paper Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch highlights a significant divide between research agendas. The study found that patients and clinicians often prioritise non-drug treatments, such as physical or psychological therapies, while researchers tend to focus on drug treatments.

Specifically, only 18% of the treatment priorities identified by patients and clinicians were drug-related, compared to 37% in non-commercial trials and 86% in commercial trials. The authors emphasise the need for the research community to better align with the priorities of patients and healthcare professionals, advocating for increased efforts to address issues most relevant to those directly affected.

Comparison of Research Priorities: Nature Reviews Neurology vs. Trip Database Blog

I’ve compared the research priorities outlined in Nature Reviews Neurology (“Parkinson Disease Therapy: Current Strategies and Future Research Priorities”) with those in the Trip Database Blog (“Identifying Research Gaps in Parkinson’s Disease – Prioritised”). Below is a breakdown of where they align and where they diverge.

1. Shared Research Priorities

1.1 Early Detection & Biomarkers

Both sources emphasize the importance of developing reliable biomarkers for early diagnosis and monitoring disease progression.

- Nature Reviews Neurology focuses on integrating sensitive biomarkers (biofluid, imaging, digital) to track disease progression and support early intervention.

- The Trip Database Blog highlights the need for non-invasive biomarkers (e.g., saliva, blood, microbiota) to improve accessibility and reduce inequities in early detection.

1.2 Advancing Symptomatic Treatments

Both sources prioritize improving symptom management, particularly for motor and non-motor complications.

- Nature Reviews Neurology discusses refining deep brain stimulation (DBS), surgical, and infusion therapies to target levodopa-resistant symptoms and delay complications.

- The Trip Database Blog explores optimal exercise regimens and cognitive training interventions to improve motor function and cognitive symptoms.

1.3 Disease Modification Strategies

Both sources recognize the need for treatments that alter the disease course, rather than just alleviating symptoms.

- Nature Reviews Neurology discusses potential disease-modifying therapies, including α-synuclein-targeting treatments, neuroinflammation approaches, and genetic therapies (LRRK2, GBA mutations, GLP-1 receptor agonists like Exenatide).

- The Trip Database Blog specifically calls out GLP-1 receptor agonists (like Exenatide) as a promising intervention and highlights the need to determine which patients will benefit most from disease-modifying therapies.

2. Differences Between the Two Sources

2.1 Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) (Trip Database Blog Only)

- The Trip Database Blog explicitly prioritizes the use of AI in early diagnosis to improve accuracy and reduce misdiagnosis rates.

- Nature Reviews Neurology does not specifically mention AI, though its emphasis on biomarkers could theoretically align with AI-driven diagnostics.

2.2 Personalized vs. Population-Level Approaches

- Nature Reviews Neurology emphasizes a personalized medicine approach, tailoring therapies based on genetic and biomarker profiling.

- The Trip Database Blog is more focused on population-level solutions, such as broad biomarker screening and AI integration to ensure equitable early diagnosis.

2.3 Focus on Exercise & Lifestyle (Trip Database Blog Only)

- The Trip Database Blog highlights the need to identify the most effective exercise regimens for symptom management and potential disease modification.

- Nature Reviews Neurology does not explicitly discuss exercise or lifestyle interventions, although it does acknowledge environmental and genetic risk factors in disease development.

2.4 Deep Dive into Disease Mechanisms (Nature Reviews Neurology Only)

- Nature Reviews Neurology provides a much deeper discussion of underlying disease mechanisms, including α-synuclein aggregation, genetic mutations, and neuroinflammatory pathways.

- The Trip Database Blog focuses more on practical applications (e.g., biomarker accessibility, AI tools, and exercise programs) rather than mechanistic research.

Conclusion

Key Overlaps:

✅ Early Detection & Biomarkers – Both emphasize the importance of finding reliable, accessible biomarkers.

✅ Symptom Management – Both focus on improving treatments for motor and non-motor symptoms.

✅ Disease Modification – Both support research into disease-modifying therapies, particularly GLP-1 receptor agonists (like Exenatide).

Key Differences:

❌ AI in Diagnosis – Only Trip Database Blog prioritizes the role of AI in improving diagnosis.

❌ Exercise & Lifestyle – Only Trip Database Blog emphasizes exercise regimens as a research priority.

❌ Personalized Medicine vs. Population-Level Approaches – Nature Reviews Neurology focuses on tailored treatments based on genetics and biomarkers, while the Trip Database Blog highlights broad interventions for all patients.

❌ Mechanistic Research Focus – Nature Reviews Neurology is heavily focused on underlying disease mechanisms, while the Trip Database Blog is more focused on applied interventions.

Recent Comments