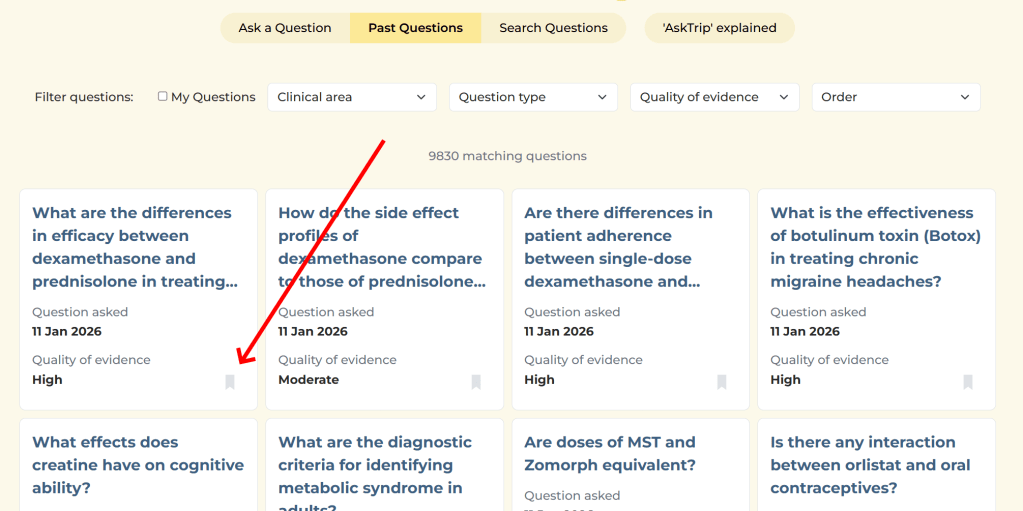

Over the past few months we’ve received hundreds of individual pieces of feedback on AskTrip answers. Around 15% were low ratings. That might sound worrying, but I actually find the low scores the most valuable.

Why? Because they’re actionable.

People who are dissatisfied are far more likely to tell you about it, so the 15% is likely to be an overestimate of overall dissatisfaction. But each low score comes with something far more useful than a number: a clue about where the product isn’t meeting expectations. And when you look across hundreds of these, clear patterns start to emerge.

Here are the main things we learned.

1. Clinicians want answers that stay tightly focused on their question

One of the most common frustrations wasn’t that the information was wrong – it was that it drifted.

A clinician might ask a very specific question (a particular population, drug comparison, route, or clinical dilemma), but the answer sometimes broadened into a more general discussion of the topic.

Interesting? Yes.

Helpful for a decision? Not always.

The lesson for us is simple: relevance beats comprehensiveness. Staying locked onto the exact clinical question matters more than covering the wider subject area.

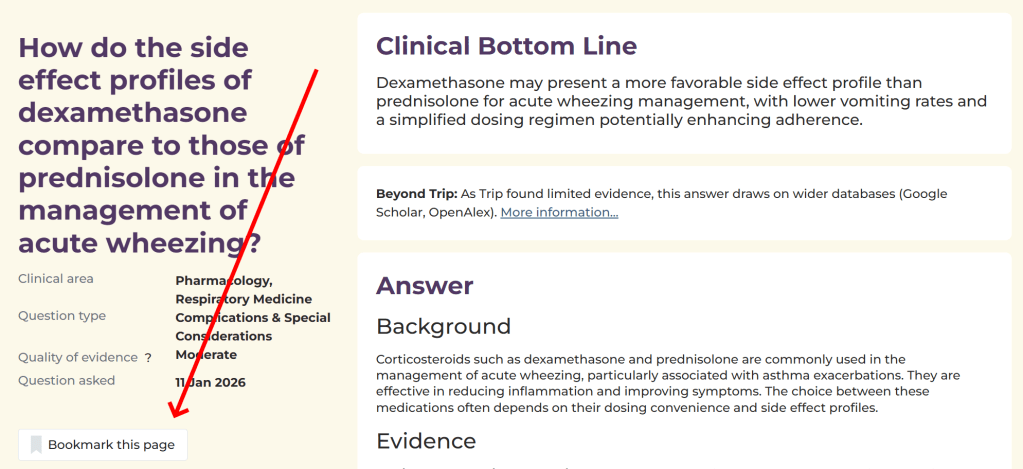

2. Confidence must match the strength of the evidence

Another pattern was what I think of as “EBM wallpaper” – answers that looked polished and evidence-based but were built on thin or indirect evidence.

Users don’t just want citations. They want honest calibration:

- Strong evidence → clear conclusions

- Limited evidence → say so early and plainly

- No evidence → don’t dress it up

In other words, clinicians value honest uncertainty more than polished narrative.

3. When the evidence isn’t there, don’t guess

Sometimes there is no directly relevant research – or the question uses a term that isn’t recognised in the evidence.

In these situations, the risk for AI is to be “helpful” by filling the gap with general advice, assumptions, or plausible definitions. That can create confident answers that aren’t actually evidence-based.

Our approach will be different. When evidence is missing or uncertain, AskTrip will:

- Say this clearly and early

- Avoid speculation or invented interpretations

- Suggest related questions that are more likely to return useful evidence

Sometimes the most helpful response isn’t a longer answer — it’s helping you ask the next, better question.

4. And finally… some people want more detail

Interestingly, the feedback wasn’t all about making answers shorter or tighter.

Around one third of users told us the opposite – they’d like longer, more detailed answers.

This highlights something important: clinicians use AskTrip in different ways. Some want a quick, decision-focused summary. Others want to explore the underlying evidence in depth.

So the challenge isn’t simply length – it’s flexibility.

What we’re changing next

This feedback isn’t just interesting – it’s directly shaping the next phase of AskTrip.

We’re actively working on two key improvements.

1. Better-calibrated answers

We’re refining how answers are generated so that they:

- Stay tightly focused on the exact clinical question

- Match confidence to the strength of the evidence

- Say clearly when evidence is limited or absent

- Avoid speculation or unnecessary narrative

2. A redesigned answer format

We’re moving toward a structure that supports different user needs:

- A concise clinical summary by default – clear, decision-focused, and quick to read

- Expandable detail – allowing users to explore the full evidence, studies, and context when they want more depth

In short:

Short by default. Deep on demand.

Why low scores are valuable

It’s easy to focus on average ratings or overall satisfaction. But the most useful feedback often comes from the edges, the cases where we didn’t meet expectations.

Those low scores aren’t failures. They’re signals.

And if we listen carefully, they help us do what AskTrip is designed to do in the first place:

Turn evidence into answers that clinicians can actually use – clearly, honestly, and at the level of detail they need.

Recent Comments