We last tinkered with the journals list in 2022, so a refresh was long overdue.

At the moment Trip takes content from PubMed in three main ways:

- A filter to ID all the RCTs in PubMed, whatever the source.

- A filter to ID all the systematic reviews in PubMed, whatever the source.

- All the articles from a core set of journals.

Core journals

When we first added journals to Trip around 1998–99, we started with 25 titles. This number grew to 100, then 450, and as of today, we include just over 600 journals. With the upcoming launch of our clinical Q&A system, we felt it was a good time to review our journal coverage with the aim of expanding it further.

We took a multi-step approach:

- The Q&A system uses a categorisation framework based on 38 clinical areas. We used these categories to identify relevant journals in each category.

- We excluded journals that do not support clinical practice—such as those focused on laboratory-based research.

- We removed journals already included in Trip.

- From the remaining titles, we selected those with the strongest impact factors for inclusion.

Additionally, since impact factors can undervalue newer journals, we manually identified promising new titles likely to be influential – such as NEJM AI – and added them as well.

The outcome of our review: we identified 281 new journals, which we’ll be adding over the next few days. This will bring our total to just under 900 journals. That feels about right—representing roughly 20% of all actively indexed journals in PubMed.

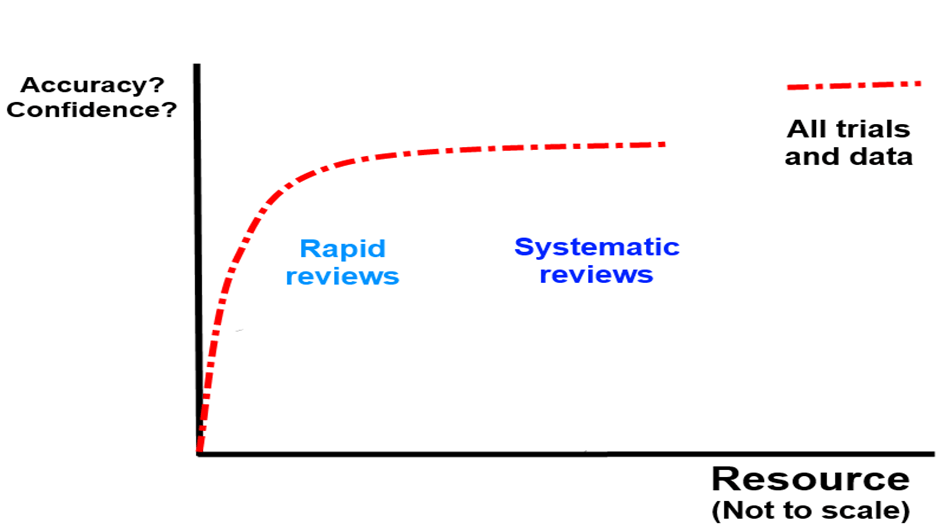

While we may continue to add the occasional journal in the future, it’s unlikely we’ll see an expansion of this scale again. There’s always a balance to strike between broad coverage and introducing noise – and we believe we’ve judged it well.

Recent Comments