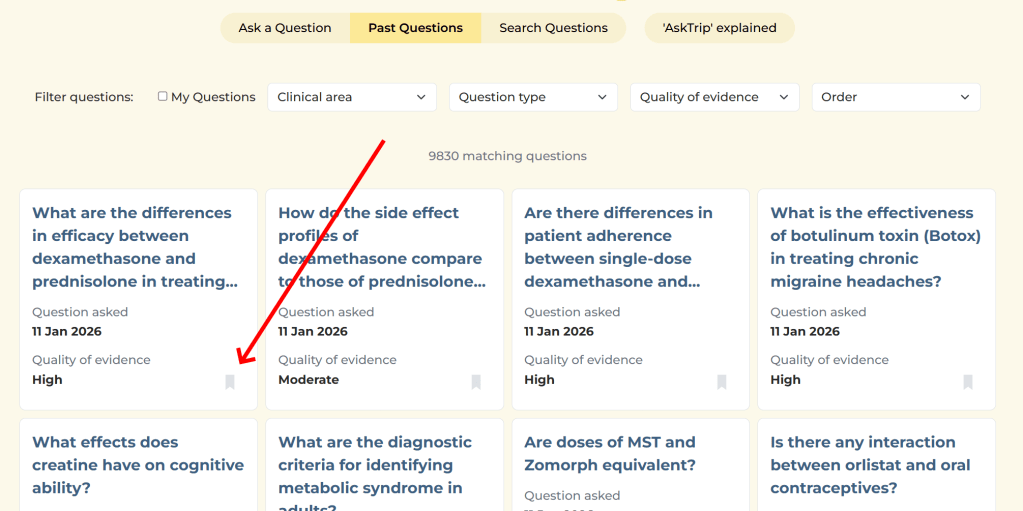

Just over six months after launch, AskTrip answered its 10,000th clinical question. Beyond being a milestone, this created a rare opportunity: to step back and look at what clinicians actually ask when given the freedom to pose questions in natural language – and what kind of evidence is available to answer them.

This post shares some of the most interesting patterns we found when analysing those first 10,000 questions, focusing on three things:

- What types of questions clinicians ask

- How those question types relate to the strength of available evidence

- How questions differ across professional groups

What emerges is a picture of modern clinical uncertainty – and where evidence serves clinicians well, and where it doesn’t.

1. Most clinical questions are about “what should I do?”

By a long way, the most common questions asked on AskTrip are about treatment and management.

Roughly one third to one half of all questions fall into this category. These include questions about:

- Drug choice and dosing

- First-line and second-line treatments

- Managing patients with specific comorbidities

- Whether an intervention is appropriate in a particular context

Diagnostic questions are much less common, typically under 10% of all questions. Prognosis questions (life expectancy, disease course, outcomes) are rarer still.

This suggests that AskTrip is primarily being used at the point of action, when a clinician is deciding what to do next, rather than earlier in the diagnostic process or later when thinking about long-term outcomes.

2. Treatment questions tend to have the strongest evidence

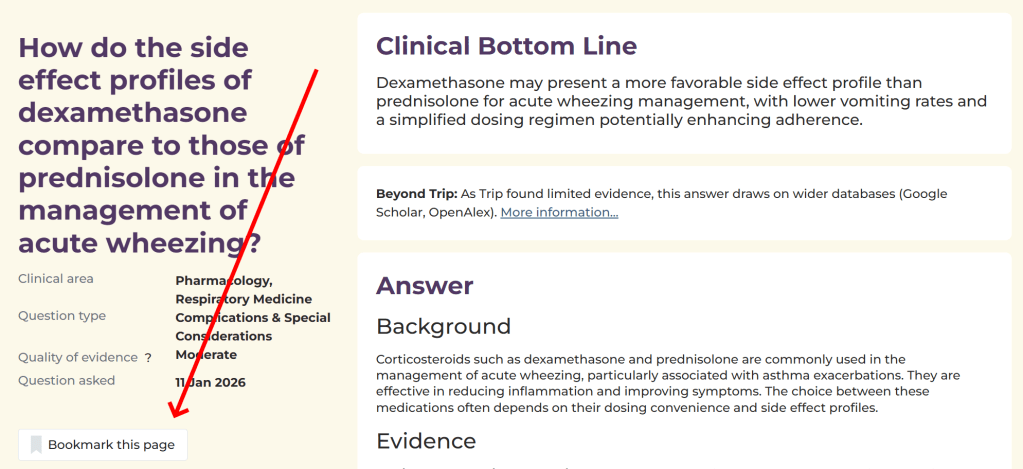

One striking finding is how closely question type aligns with evidence strength.

Treatment and management questions are far more likely to be answered using high-quality evidence – such as clinical guidelines, systematic reviews, or large trials. A substantial proportion of these answers receive a High evidence rating.

This makes sense. Many treatments for common conditions are well studied, frequently updated, and synthesised into guidelines. When clinicians ask “What’s the recommended treatment for X?”, there is often a clear evidence trail to follow.

In contrast, questions about:

- Etiology and risk factors

- Rare or unusual clinical scenarios

- Health system issues and care delivery

- Complex patients with multiple conditions

are much more likely to be answered with moderate or limited evidence.

These are the areas where research is sparse, indirect, or ethically difficult to conduct – and AskTrip’s answers reflect that reality.

Importantly, this isn’t a weakness of the system. It’s a reflection of the evidence landscape clinicians work within every day.

3. “Thin evidence” clusters in predictable places

When we looked more closely at questions rated as having limited evidence, clear patterns emerged.

Thin evidence tends to cluster around:

- Complex decision-making, such as balancing risks after serious adverse events

- Patients with multiple comorbidities, often excluded from trials

- Rare conditions, where large studies don’t exist

- Care delivery and system questions, which sit outside traditional disease-focused research

These are the situations clinicians typically struggle with most, not because they are uncommon, but because they don’t fit neatly into trial designs.

In other words, the hardest clinical questions are often the ones least well served by research, even though they matter deeply to patients and clinicians alike.

Seeing these gaps at scale helps move the conversation away from “why don’t we have an answer?” toward “why is this so hard to study – and what should we do about it?”

4. Different professionals ask different kinds of questions

AskTrip is used by a wide range of healthcare professionals, and their question patterns differ in telling ways.

Doctors ask the majority of questions, and their focus is overwhelmingly on treatment decisions. Diagnostic questions appear, but less often. Prognosis questions are rare.

Pharmacists ask fewer questions overall, but theirs are the most tightly focused. The vast majority are about medications – dosing, interactions, safety, and comparative effectiveness. Diagnostic and prognostic questions are almost absent.

Nurses ask fewer “classic” clinical questions and more queries that sit outside neat categories —- for example:

- Practical aspects of care

- Clinical measurements and interpretation

- Protocols, safeguarding, and service delivery

As a result, a higher proportion of nursing questions fall into “other” categories and are more likely to involve moderate or limited evidence.

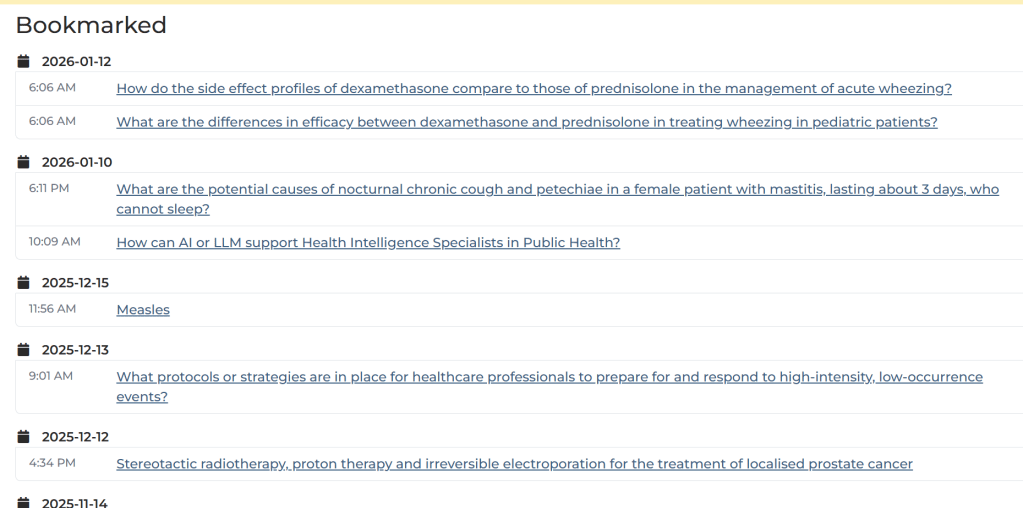

Information specialists and librarians ask a distinct set of questions on AskTrip. Their queries often focus less on a single clinical decision and more on understanding the shape and strength of the evidence – for example, whether high-quality studies or guidelines exist on a topic, or where evidence is thin or conflicting. In this sense, AskTrip appears to function as a rapid evidence-triage tool, helping information specialists quickly gauge what is known before undertaking deeper searches, synthesis work, or supporting clinicians’ decision-making.

This isn’t accidental. It reflects professional roles and responsibilities. Each group uses AskTrip to fill different kinds of gaps – and that diversity of use is one of the platform’s strengths.

5. What this tells us about evidence-based medicine

Looking across 10,000 questions, a few broader lessons stand out.

First, evidence-based medicine is working well where research, guidelines, and synthesis are mature – particularly for treatment decisions in common conditions.

Second, uncertainty hasn’t gone away. It has simply moved into more complex, contextual, and system-level spaces where traditional research struggles.

Third, clinicians are not just asking “What does the evidence say?” – they are asking:

- “Does evidence exist for this situation?”

- “How confident should I be?”

- “What do we do when evidence is thin?”

Finally, surfacing where evidence is limited is not a failure. It’s a necessary step toward more honest decision-making – and toward identifying priorities for future research.

Closing thought

AskTrip was built to lower the barriers to high-quality evidence. But these 10,000 questions show something equally important: they map the boundaries of our knowledge.

They show us where evidence is strong, where it’s weak, and where clinicians are navigating uncertainty every day.

That, in itself, is evidence worth paying attention to.

Recent Comments