At AskTrip, we are committed to protecting your privacy and using data responsibly. The following explains what information we collect, how we use it, and how we safeguard it.

What We Collect & Why

When you use AskTrip—either by logging in or accessing the service via IP authentication—we log your user ID (or institution ID) and IP address. This applies both when submitting questions and when viewing answers.

We collect this data to support service delivery, session management, usage monitoring, abuse prevention, and auditing. Question content and associated metadata are retained only as long as necessary for operational reasons (currently 90 days), unless selected for internal quality assurance or audit purposes.

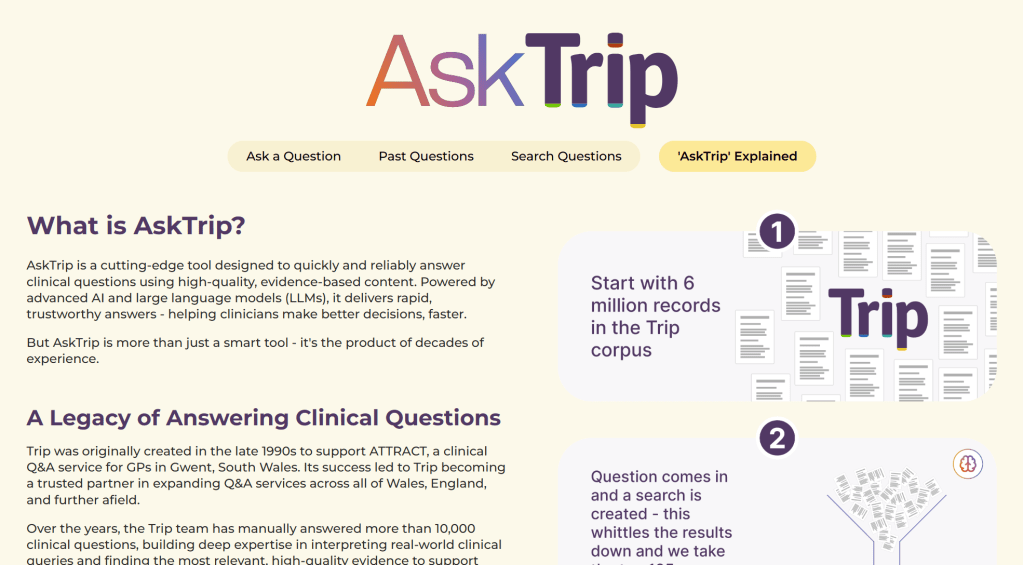

Processing by Large Language Models (LLMs)

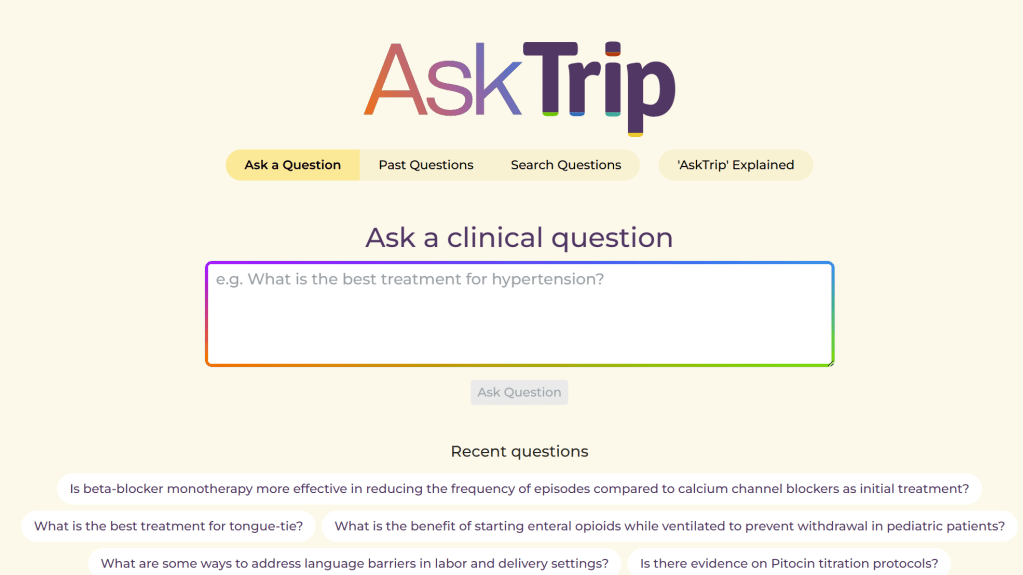

AskTrip uses external large language models (LLMs) to generate optimized search terms based on user-submitted questions. These models receive only the text of the question—we do not send login details, IP addresses, or any other user-identifying information.

However, if a user includes personally identifiable information (PII), such as a patient’s name or date of birth, this content will be sent to the LLM before AskTrip’s redaction layer can act. While the LLM may label such data as sensitive, it cannot be withdrawn once submitted.

Internal Query Handling

After the LLM generates search terms, all further processing happens securely within AskTrip’s systems. We search our internal clinical database (Trip Database), extract key clinical findings, and return an evidence-based summary to the user. No user-identifiable information is involved in this step, and no external systems access your data.

Analytics & Reporting

We use system logs, including user IDs, institution IDs, and IP addresses, to generate analytics reports that help us improve performance and understand usage trends. These reports are anonymized and aggregated.

Only authorized Trip staff can access raw log data, and it is never shared with external parties or visible to other users.

Use of Data for AI Development

We currently do not use any user-submitted data or usage logs to train or fine-tune AI models.

If this policy changes in the future, we will update this statement in advance and offer users the ability to opt out of such use.

Identity & Integration

AskTrip operates as a standalone service. It does not currently integrate with external identity providers such as Microsoft 365 or Google Workspace. User authentication is managed directly by AskTrip or through IP-based access provided by your institution.

Secure Access to Information Sources

AskTrip accesses only licensed or publicly available content from the Trip Database. All queries to our content sources are performed in read-only mode. No external system can access your queries or the content returned by AskTrip.

Data Security & Compliance

All data transmission is encrypted using industry-standard protocols (e.g., HTTPS/TLS 1.2+). Our hosting infrastructure is provided by Amazon Web Services (AWS), which is certified under standards such as ISO/IEC 27001 and SOC 2.

While the hosting platform meets these standards, the AskTrip application itself is not yet ISO/IEC 27001 certified—but we are actively working toward this. We comply with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and other relevant data protection laws.

Responsible Use

AskTrip is not intended to process or store sensitive personal data. We strongly advise users not to submit queries containing patient-identifiable information, such as names, dates of birth, or NHS numbers.

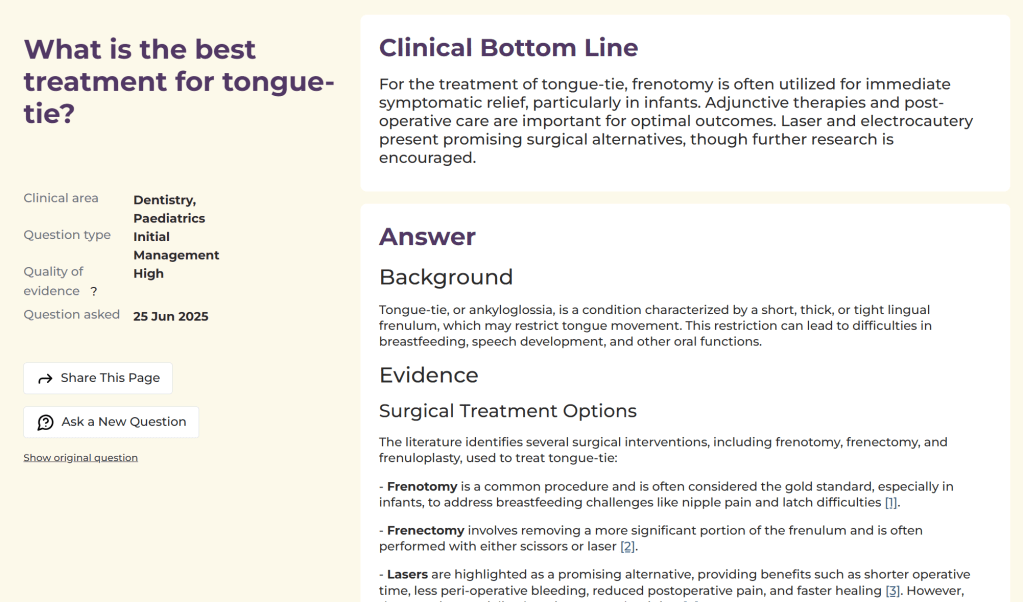

Clinical Decision-Support Disclaimer

AskTrip is designed to support – not replace – clinical decision-making. The information it provides is intended to aid professionals but does not substitute for individual clinical judgment.

This disclaimer applies to all users, including those who view previously answered questions, not just the original question submitter.

Enterprise Deployment Options

For institutional partners, AskTrip offers tailored deployments, including private hosting, single-tenant environments, data segregation, and custom retention policies, to meet specific governance, compliance, and security requirements.

Recent Comments